The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) has deep roots in the labor movement along the West Coast of the United States. Formed in 1937, it emerged from a time when longshore workers and warehouse employees endured brutal working conditions. Dangerous job sites, low wages, and exploitative treatment were common, with companies viewing longshoremen as easily replaceable.

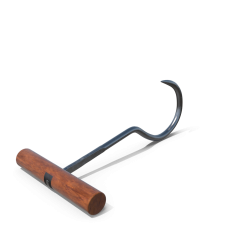

Back then, a longshoreman’s most essential tool was the "T Hook" or "Hay Hook"—a long-handled, curved hook with a sturdy T-shaped grip. It was used to manually load and secure heavy cargo like cow hides and ice blocks deep within the holds of ships. Working in hazardous environments, longshoremen relied on their skill and strength to get the job done. Over time, the T Hook came to symbolize both the physical demands of their work and the unity they shared on the docks. Today, it’s known simply as the "Longshore Hook"—an enduring emblem of resilience.

The fight for better conditions and fair wages reached a turning point during the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike. Workers stood together in a bold show of solidarity, refusing to back down despite violent opposition. On July 5, 1934, now remembered as "Bloody Thursday," two striking workers were killed in San Francisco during clashes with riot police. Their sacrifice became a rallying cry, fueling the resolve of longshoremen across the coast. To this day, ILWU members gather every year on July 5th to honor the memory of those who gave their lives in the fight for justice.

Guided by influential leaders like Harry Bridges, the ILWU grew into a powerful voice for workers' rights. Bridges, known for his unwavering dedication to the labor movement, led efforts to unite workers of all backgrounds. The ILWU’s commitment to equality and inclusion stood out during an era of widespread discrimination. The union welcomed people of all races and backgrounds, emphasizing that true strength comes from standing together.

The ILWU’s motto, "An Injury To One Is An Injury To All," remains a defining principle. It speaks to the belief that when one worker suffers injustice, it affects everyone. This sense of collective responsibility has fueled the union’s work not only in the maritime industry but also in agriculture, fishing, warehousing, and other sectors. The ILWU expanded its reach to represent workers in Hawaii, Alaska, and Canada, amplifying the voices of thousands.

Today, the ILWU continues to advocate for fair labor practices, safe working conditions, and equitable treatment. While modern machinery has largely replaced the physical strain of the past, the spirit of solidarity remains. The Longshore Hook has shifted from a tool of labor to a symbol of pride and remembrance — a nod to those who built the union through their sweat, determination, and courage.

Every victory and advancement the ILWU has achieved is a testament to the power of collective action. The challenges faced by past generations serve as a reminder of what can be accomplished when workers stand together. As the ILWU moves forward, it carries with it the legacy of those who fought for fairness and dignity — proving that the spirit of the longshoremen lives on, strong as ever.

Harry Bridges stands as one of the most influential figures in the American labor movement. Known for his fierce dedication to dockworkers and warehouse laborers on the West Coast, he played a key role in creating and leading the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). His legacy is one of resilience — standing up for fair treatment of workers, organizing powerful labor actions, and ensuring that longshore and warehouse employees had a strong voice on the job.

Born on July 28, 1901, in Kensington, Melbourne, Australia, Bridges grew up working a variety of labor-intensive jobs. After spending time as a seaman, he made his way across the Pacific and arrived in San Francisco in 1920. He was drawn to the bustling waterfront, where he quickly saw firsthand the brutal conditions faced by dockworkers — low wages, hazardous work environments, and job insecurity were the norm.

Seeing the need for change, Bridges became deeply involved in labor activism. His time at sea and on the docks had shown him the importance of unity, and he was determined to fight for fair treatment of waterfront workers.

By the early 1930s, workers on the waterfront were at a breaking point. Conditions were harsh, and employers held all the power. Bridges and other activists responded by organizing longshoremen into International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) Local 38-79 in 1933. Under his leadership, the local quickly grew in strength and numbers.

Bridges and his fellow organizers worked to unite a diverse workforce, including many immigrants who faced additional challenges on the job. Together, they fought for better wages, safer working conditions, and job security. The movement gained momentum, setting the stage for the most defining moment of Bridges’ career.

The struggle for fair treatment came to a head during the 1934 West Coast Maritime Strike. What began as a local labor dispute grew into a powerful, coast-wide movement as dockworkers from San Francisco to Seattle demanded fair wages, an end to employer favoritism, and safer working conditions.

Bridges emerged as a leading voice of the strike, helping to coordinate and unify the efforts of thousands of workers. The strike’s most tragic day, July 5, 1934, became known as “Bloody Thursday” after police killed two strikers during violent clashes in San Francisco. The loss of their lives only strengthened the resolve of the workers. Each year, ILWU members continue to honor Bloody Thursday as a day of remembrance and solidarity.

Recognizing the need for a stronger, more unified union, Bridges helped form the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) in 1937. Unlike its predecessors, the ILWU represented both longshoremen and warehouse workers, bringing them together under one powerful organization. Its goal was clear — to protect workers’ rights, ensure fair wages, and fight against unfair treatment on the docks.

Bridges continued to lead the ILWU for decades, advocating tirelessly for fair labor practices. Under his leadership, workers gained significant improvements in wages, working conditions, and job security. He retired in 1977, leaving behind a stronger, more empowered union.

But his influence reached beyond labor negotiations. Bridges was also a champion of racial and social equality. He rejected discrimination within the labor movement and pushed for the ILWU to stand in solidarity with workers of all races and backgrounds. His belief that “An Injury to One is an Injury to All” became a defining principle of the ILWU — a motto that continues to inspire labor activists today.

Harry Bridges passed away on March 30, 1990, but his legacy lives on. The ILWU remains a powerful advocate for workers’ rights, guided by the principles he championed. From the cargo docks of the West Coast to warehouses and beyond, the strength of collective action that Bridges fostered continues to protect and uplift working people.

His story serves as a reminder that the fight for dignity and fairness in the workplace is ongoing. The courage and resilience he showed in the face of adversity remain an inspiration to all those who believe in the power of unions and the enduring importance of standing together.